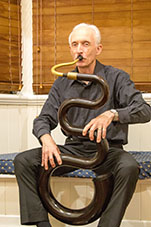

If you are wondering what the tortuous instrument is that I’m pictured playing, it is called a serpent. It is the grandfather of the modern tuba, the father being an instrument called the opheclide, Greek for keyed serpent, an instrument that looks like a saxophone crossed with a tuba. Some call it the bass of the cornetto described elsewhere on this website. The serpent is nearly two and a half metres long and has an expanding or conical bore and so can also be classified as a bugle horn. On a good day with a wind behind it, it has a range of over 2 ½ octaves from the G above middle C to the C two octaves below middle C. With only six fingerholes and no thumbhole, it is able to play all the chromatics within this range. It is made of two halves carved out of big blocks of wood glued together and then bound by a thin layer of calf leather. It has a brass crook and a cupped mouthpiece.

The serpent was invented by Edme Guillaime, a Catholic Canon in France around 1590. He was encouraged by his bishop to adapt the tenor cornett to the function of accompanying plainchant – and it’s warm tone suits it to this purpose. It was played in churches and later on horseback as a military instrument and also in the early orchestra until the mid 19th century when it was superseded by the opheclide.

I have a longstanding fascination with the serpent, but always thought they were impossible to play in tune, so refrained from buying one until after I went to the Historic Brass Symposium in New York in 2012. There I heard the inspiring performance by two leading serpent players, Doug Yeo and Volny Hostiou at the last year convinced me otherwise, so I approached and American serpentologist, Craig Kridel to buy his Harding serpent. This was a fibreglass replica and has been clothed by my long-suffering wife as she has tolerated me learning this instrument.

In 2014 I went to my first serpent workshop in a tiny village in Switzerland – one has to travel a long way to find like-minded serpent players. There were about 30 there – probably about half of the world’s serpent players and we played everything from renaissance church music through to modern jazz. I have since been to a ‘Serpentarium’ in a little town near Edinburgh, Scotland, in 2017, to play lots of wonderful serpent music with about a dozen other serpent enthusiasts.

In his book on the tuba family Clifford Bevan states that there is no question that the serpent is the most difficult of all the cup mouthpiece instruments to play to an acceptable standard. This is due to a combination of its rapidly expanding conical profile, a cup mouthpiece for generating the sound and side-holes for changing the pitch creates a unique timbre. The intonation is best for the fundamental and its harmonic series. So it works best as a kind of bugle horn.

However it is the notes between the harmonics that are the big challenge in taming this beast. For the beginner there is often considerable variation in the volume and tone of the notes as they go up and down the scales, but this evens out somewhat with practice. There is a need to lip many notes one way or the other to get all the notes. Some notes can be bent by more than a fourth, so the player needs to have a very keen sense of intonation. Consequently it is difficult to play in tune and so has been the target of some rather unkind critics in the four centuries that it has been around

In his book of orchestration, Evans said that “the serpent was such an odious affair that nothing short of compulsion could explain its employment.”

Burney in the early nineteenth century described the serpent as “a great hungry, or rather angry, Essex calf’, after an unfortunate experience in Antwerp where the serpent was’over-blown and detestably out of tune.”

The 19th century composer Hector Berlioz, who actually included the serpent in many of his orchestrations, once said: “The essentially barbaric timbre of this instrument would have been far more appropriate to the ceremonies of the bloody cult of the Druids than to those of the Catholic religion.”

“The essentially barbaric timbre of this instrument would have been far more appropriate to the ceremonies of the bloody cult of the Druids than to those of the Catholic religion.”

— Hector Berlioz —

Forsyth as recently as the 20th century wrote with schoolboy glee of the instrument which “presented the appearance of a dishevelled drainpipe which was suffering internally” (Orchestration, London 1914 – 1935)

Given this description I thought it prudent to send my first serpent along for a colonoscopy and the report came back from the gastroenterologist saying that he had spotted rudimentary elements of a French horn, a bassoon and a tuba within its workings and with a somewhat kinky twist also noted a small vibrator. That explains why it sends a nice shiver up the left thigh when you play one of the Cs.

So given the challenge of playing the serpent in tune, you realise that the most important parts of this instrument are not the fingerholes, but the lips and brainbox attached to the upper end. It often amuses me how I can play roughly the right note even when I put down the wrong fingers!

All this aside, a serpent played by a proficient musician can be a joy to listen to.

Below is a link to some inspiring serpent playing by Patrick Wibart from France. Patrick is probably the world leader in intonation, expressiveness and virtuosity on the serpent

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n-Sbq-XL_VU

Tota pulchra es – Serpent (Giovanni Bassano, Palestrina )

www.youtube.com

Ensemble Anamorphoses : Tota Pulchra es Bassano , Palestrina Patrick Wibart : Serpent Romain Falik : Théorbe Justin Glaie : Archiluth Enregistrement en concert à l …

And here is a link to Doug Yeo from the USA who has done more to promote and teach the serpent than anyone else I know. It also shows off a serpent with a snake skin pattern on it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LE93PqbuRvM

Douglas Yeo plays the serpent – video 2

www.youtube.com

This video shows Douglas Yeo, bass trombonist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, playing the serpent. He is playing a French church serpent by Keith Rogers …

If you would like to learn more about the serpent, feel free to visit the following website, but beware, the snake charmer may get you under his spell as he has long done to me.

www.serpentwebsite.com

Copyright EMSQ 2019